From the Iowa State Memorial Union:

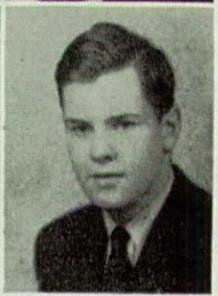

Private William Atle Nelson was born in Gary, Indiana on August 11, 1925 to Forrest A. Nelson and Virginia K. Kelly. He later lived in Galesburg, Illinois. William entered service on October 1, 1943 at Camp Dodge, Iowa. He served with Company K, 397th Infantry, 100th Division, Seventh Army. He had been in service one year, two months and four days before he was declared missing in action in France on January (should be Dec.) 5, 1944. After several months, the war department declared him to be killed in action.

From the WW2 Army Enlistment Record:

Term of Enlistment: Enlistment for the duration of the War or other emergency, plus six months, subject to the discretion of the President or otherwise according to law.

The dates are unclear, but William is said to have died during the Battle of the Bulge, Adolf Hitler’s “last major offensive in World War II against the Western Front”.

We will never know what happened to William, or how he died. He was just a kid. Had he lived until he was 20 he would have seen the war in Europe end in May, 1945. But, he didn’t. He died at 19, in all likelihood cold and scared.

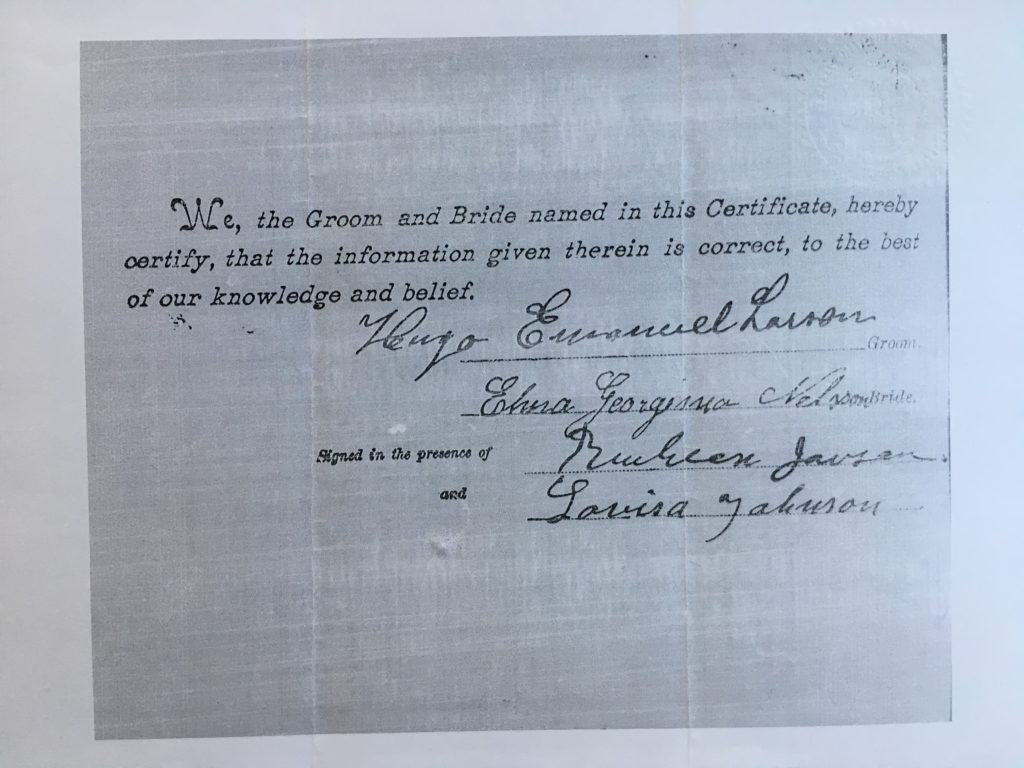

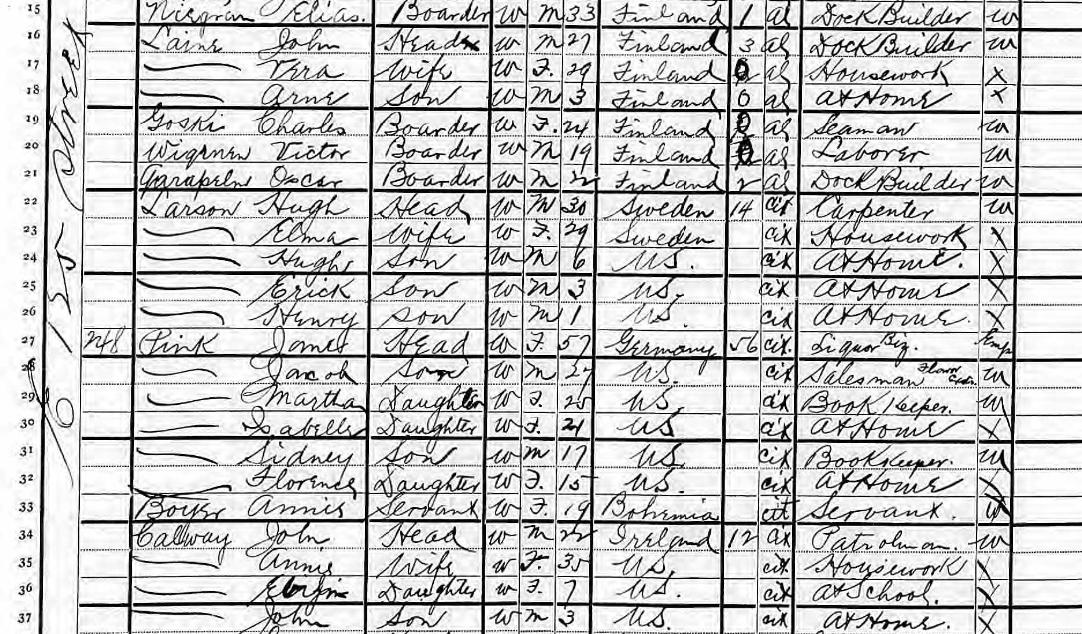

William was my seventh cousin. We are related through two brothers, Carl Månsson born 1720, and Nils Månsson born 1727. William’s grandmother Hilma Charlotta Nilsdotter emigrated from Döderhult in Kalmar county to Galesburg, Illinois in 1868. She was three years old. Hilma was the great great great granddaughter of Carl Månsson. My grandmother Herta Viktoria Nilsson was born in Döderhult, Kalmar, in 1884. She was the great great great granddaughter of Nils Månsson.

Through Carl’s and Nils’ great great grandfather, Carl Jönsson Sabelskjöld, William and I have a known shared history going back to the early 1500s.

The Sabelskjöld family website provides more information about Carl and Nils Månsson, and their family history.